On June 17, 2019, the Westerly Sun published an article about the Rhode Island Slave History Medallions Project. The goal of the project is to identify and mark sites that have historical ties to slavery in Rhode Island. The article made me interested in learning more about Rhode Island’s ties to slavery, a story relatively untold.

Rhode Island Laws on Slavery

In 1652, Rhode Island officials in Providence and Warwick attempted to prevent slavery by limiting the time that anyone could be held in bondage. The new law quickly crumbled as Providence and Warwick failed to persuade Portsmouth and Newport to accept the legislation.

In 1708, the Rhode Island General Assembly endorsed and protected race-based slavery through race laws. The abolishment of slavery in RI would not come until 1842, only 19 years before the start of the American Civil War. The story of slavery in Rhode Island is an interesting one, which reflects the larger, overarching story of slavery in the Americas.

Rhode Island and the Atlantic Slave Trade

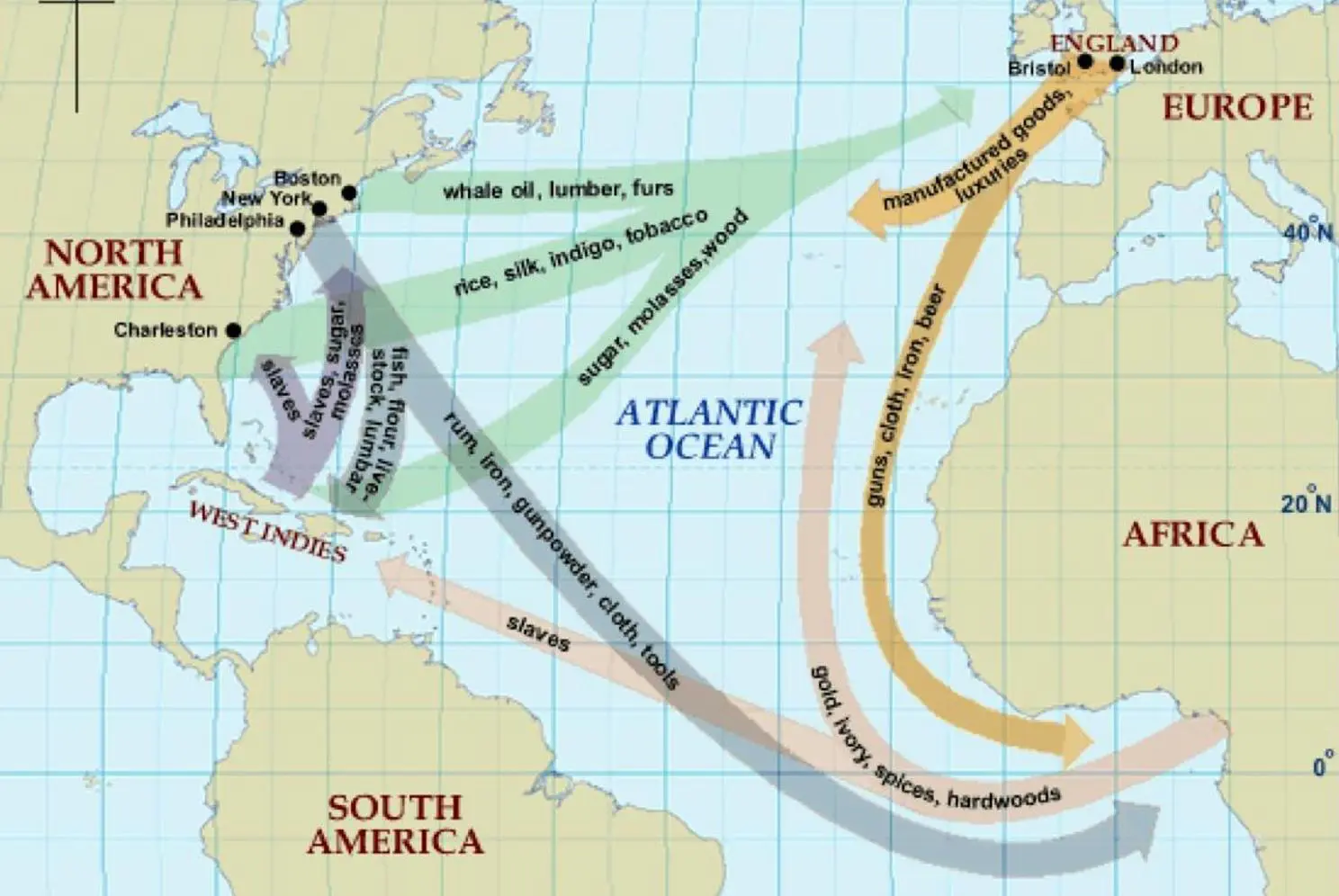

It didn’t take long for Rhode Island to become a crucial point in the triangle. Rhode Island would buy molasses and sugar from the South and would produce rum which would be traded for more slaves overseas. Eventually, Rhode Island became even more involved in the trade by building the RI slave trade.

Not only was Rhode Island sending slave ships to Africa and financially supporting the institution of slavery, but Rhode Islanders also owned slaves. The first evidence of Rhode Island importing slaves directly from Africa was in 1696. Slaves were sold at auction houses in Newport located, “at the corner of Mill and Spring Street as well as North Baptist and Thames Street.”

Most were sold to Newport merchants and tradesmen, but a significant number were sold to Narragansett farmers. By 1755, Rhode Island held the highest percentage of slaves in New England at 10 percent.

Westerly and Slavery

Slavery was not just confined to Newport and Narragansett, Westerly also had slavery. According to a report by Preservation RI, in 1669, when RI was incorporated, it only had “30 white families” and Westerly included today’s Charlestown, Richmond, and Hopkinton. Charlestown wouldn’t become independent until 1738, and in 1757 Hopkinton became independent. Despite the relatively small population in Westerly’s founding, there are a multitude of recordings of slaves in Westerly, mostly by those who were wealthy and had the means to buy a slave.

Wealthy Westerly residents fell into an interesting paradox, one that consumed Colonial America. Colonial officials preached and fought for independence from England, citing liberty, freedom and self-government, all the while defending slavery and the right to profit from the institution. Two excellent examples of Westerly elites falling into the slave trade includes Samuel Ward and Joseph Noyes.

Samuel Ward was Governor of Rhode Island and later a delegate for the Continental Congress. While in Philadelphia with the Continental Congress he contracted Smallpox and died. Reportedly at his bedside was his slave, Cudjo. Following Ward’s death, Cudjo and Ward’s second slave Peggy were inherited by Oliver Wilcox.

Joseph Noyes was another Westerly Statesman and owned seven slaves. He and Joshua Babcock were members of the House of Representatives of Rhode Island who in 1776 voted “to repeal an act for the maintenance of the King’s authority in Rhode Island.” This was prior to the Declaration of Independence, making Rhode Island the first sovereign nation in the western world.

The reasoning for Rhode Island’s early departure from England was largely due to the Sugar Act. Since Rhode Island largely profited in the triangular trade by producing rum from the sugar coming from the South, they saw the tax as a threat to their way of life. Therefore, Rhode Island’s freedom from Great Britain meant merchants could have financial freedom, continue becoming wealthy, all the while strengthening the bonds of slavery.

By 1755, Rhode Island found itself completely engulfed in the slavery paradox, in a similar position that led to Thomas Jefferson’s famous quote in 1820 about slavery “we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go.”

Rhode Islanders found themselves engulfed in the trade, fearing if they let go, they would become bankrupt and society would crumble. While we know today that this is not true, to Rhode Islanders of that time, it might as well have been true.

The End of Slavery

It wasn’t until the 1770s that Rhode Islanders would start to see slavery as immoral. The Quakers who were originally seen as outcasts and heretics in New England society started to penetrate the societal hierarchy. Moses Brown, once a huge proponent of slavery, in 1773 converted to Quakerism and freed his 10 slaves and called on others to do the same. In 1784, Rhode Island passed the Gradual Emancipation Act, “children born to slave mothers were to be considered freeborn citizens. However, to compensate owners for their losses, such children were to be bound out as apprentices until age 21, and their wages paid to their mothers’ owners.

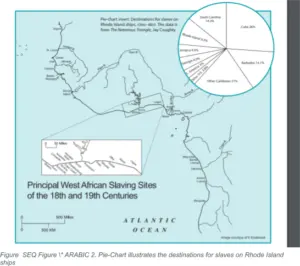

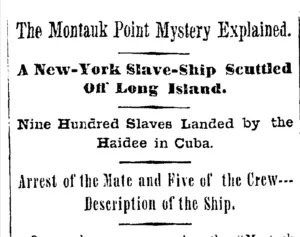

Later in 1787, Rhode Island made it illegal for Rhode Islanders to be involved with the African slave trade anywhere. In 1788, Moses Brown and Samuel Ward convinced Connecticut and Massachusetts to do the same. Despite these laws in the books, few followed or enforced them. Rhode Islanders involved in the slave trade would find ways around the laws, often by buying whaling ships and transform them into slave ships. Instead of bringing the slaves to Rhode Island, they would sell the slaves to Cuba before returning to RI.

Significance

Slavery is not a pleasant history; many would rather remove it from the history books than have to learn and teach about it. As difficult of a subject, the impact of slavery is still felt today, manifesting in different ways. To not understand and learn about Rhode Island’s role in slavery is an injustice.

History is a rather complex narrative, with an untold number of characters, settings, and plots. Like with any story, if a few pages are ripped out, the plot still may make sense, but the reader is still left with questions and the story feels incomplete.

It’s the same idea with history. History needs to be looked at holistically, the bad needs to be understood before the good can be appreciated. While Rhode Island and Westerly eventually became involved with antislavery and the abolition movement, the previous chapters need to be comprehended before the next chapters can be understood.