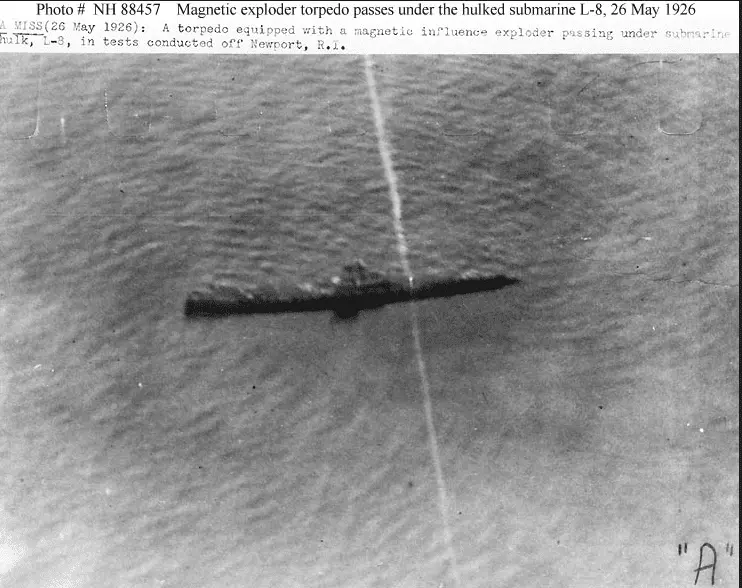

A gentle swell rocked the Thunderfish as Captain Bill positioned the boat over the wreck of the L-8 which was sunk in 1926 by a magnetic torpedo. Captain Bill called out, “OK, let her go.” Out on the bow, Tommy dropped the grapple and Captain Bill reversed the engines until Tom yelled, “I’m hooked up,” meaning the grapple which had been dragged over the wreck had caught on it. A diver would still have to go down and tie the grapple to the wreck to make the Thunderfish secure. The crew would not want to surface only to find that the boat had broken lose and drifted away. It was a long swim to shore.

The L-8 was one of the submarines designed by Simon Lake and was the first submarine ever built by the US Navy. Lake was a prolific inventor and many consider him the father of the modern submarine. In 1895 Lake built the Argonaut, a 36-foot submarine that was the first to operate in the open sea. The sub also had wheels which allowed it to travel on the ocean floor and a door that allowed a diver to exit and enter through an open hatch. In 1898 the Argonaut made a two-thousand mile journey from Norfolk to New York that brought a congratulatory telegram from Jules Verne to Simon Lake.

Lake formed the Lake Torpedo Boat Company in Bridgeport, Ct. in 1901 and manufactured the Protector. The Protector was a type of military submarine which was built for the United States and for other foreign governments. Lake provided consultation services to various countries and maintained offices in Russia, Germany, Poland, Austria, and England. He shared part of his London office with the Wright brothers. The inventors first met when the Wright brothers submitted their airplane designs to Lake for his opinion. Lake’s success in Europe led, with the unfolding of WWI, to the US government requesting his services so he returned home to build submarines for the US Navy. Today’s dive would take Captain Bill and the other divers back to that time.

“OK, let’s suit up and go diving,” Captain Bill called. The noise of the diesels died and a flurry of activity took over the boat as the four wreck divers started the process of putting on their gear.

I watched the divers get into their dry suits and strap on tanks. The amount of equipment an open ocean diver has to use would make even the most ardent hobbyist cringe. The divers donned their suits over long underwear, hoods, gloves, tanks, computers, regulators, cameras, bags, face masks, knives, wreck reels, and finally a 30 pound weight belt. I told Bill he looked like a mix between a penguin and an astronaut. Bill smiled and recalled, “My father used to tell me that I should wear a suit but I don’t think this is the kind of suit he had in mind.” A wreck diver has around 130 pounds of gear to carry and in their dry suits the divers are dripping sweat as they finish their prep. Then, one by one they jump off the stern and disappear under the surface.

As Bill finishes dressing I hand him his video camera as he awkwardly climbs over the transom to the swim platform. Grabbing the safety line he jumps into the water and floats around for a minute doing a final check then slowly disappears under the surface with only his bubbles marking the spot.

Captain Bill descends the anchor line and the light begins to fade. In the darkness, the L-8 gradually appears like a ghost ship from another time. “I pull myself down the anchor line behind my partners. It’s dark, but better visibility than I’m used to. The conning tower looks like a 55-gallon drum compared to the subs of World War II and on the side of the conning tower, there are glass slits. It’s possible that these were viewing ports.

The captain could have looked through them to see when the decks were awash. I start to swim forward and directly in front of me is a hatch which leads into the galley area. A quick look inside and then I continue to move forward. Directly in front of me is the forward torpedo loading hatch. It comes up off the deck on a 45-degree angle. What I’m seeing now is just the pressure hull because the outside deck casing has mostly rusted away. I’m amazed that in some spots the deck is still intact after being submerged for 93 years.”

“I swim up to a huge hole in the hull that is where the torpedo struck. I’m amazed that this sub was almost completely blown in half. I enter the hole being careful not to dislodge the silt which would result in not being able to see and swim forward to where the torpedoes were stored. In the distance, I can see the doorway that leads into the galley and the crew’s quarters. The door is lying on the floor apparently blown off its hinges by the explosion.

At one time this area was filled with piping, cabinets and equipment but now there’s nothing but mud and silt. It’s a tight squeeze to try and get through these bulkheads with a pair of tanks on your back, being careful to not get hung up on something. There’s so much silt inside this boat that it almost completely fills some of the compartments. It’s a difficult dive, at times we have to fight our way through entanglements and zero visibility. I swim forward being careful not to disturb the thick silt which then becomes a blinding snowstorm. Modern submarines have watertight doors. There doesn’t seem to be a single watertight door on this boat.”

From onboard the Thunderfish I’ve been watching bubbles break the surface as the divers explore the wreck. I have time to think about Simon Lake and his vision for the submarine. Lake promoted peaceful uses of his submarine technologies for the benefit of mankind but governments chose the submarines for military use instead. Lake envisioned farming the natural resources of the sea, harvesting edible foodstuffs, pearls, sponges, gold, and other minerals. He designed cargo submarines for safe and efficient transport of oil and other cargoes.

In 1930 Lake joined forces with Sir Hubert Wilkens, the famous polar explorer, in the first Trans-Arctic Submarine Expedition in an attempt to reach the North Pole under the Artic ice. The purpose was to explore under-ice passageways for the use of commercial submarines through northern routes.

The expedition acquired the O-12 built-in 1918 by The Lake Torpedo Boat Company. The vessel was re-outfitted for the arctic expedition and christened the Nautilus in 1931 by Jean Jules Verne, the grandson of the famous author. The Nautilus set sail for the North Pole on June 4, 1931. She successfully toured an area of the arctic region and was the first submarine to go under the Arctic ice. It wasn’t until 1958, 27 years later, that on her third attempt the nuclear-powered submarine Nautilus successfully traveled under the ice to the North Pole.

After what seems like ages I finally see a divers head appear and one by one the divers emerge from the sea, almost like Captain Nemo’s men in his book. Obviously it’s been a great dive and the divers excitedly compare stories. One of them got hung up on some piping and could have been in trouble except for help from his buddy. Captain Bill is last to emerge and is helped onto the boat looking tired but happy.

“Wow, what a dive! I think I’ve got some incredible footage. I still can’t believe how small that conning tower is, like a 55-gallon drum. You know, going down that anchor line is like going back through the pages of history to almost 100 years ago. This suit and my equipment is my time machine.”

The crew wastes no time in getting the boat underway and Captain Bill set a course for the Mystic River. Sitting at the helm steering the Thunderfish he seemed reflective,

“You know, I think Simon Lake would be sad to see his ideas for the submarine used for war and not for peaceful purposes. I also wonder what Jules Verne would think about Lake’s success in bringing his vision of men working under the sea to life. Lake truly was the father of the modern submarine and the real Captain Nemo.”