Although slavery is a significant part of the history of the United States, it played a much smaller role in New England than it did throughout most other parts of the nation. As a result, slavery was rare in Westerly throughout much of the town’s history. In 1790, there were ten slaves recorded across four households. In every census record available after 1790, not a single slave was enumerated in Westerly.[1]

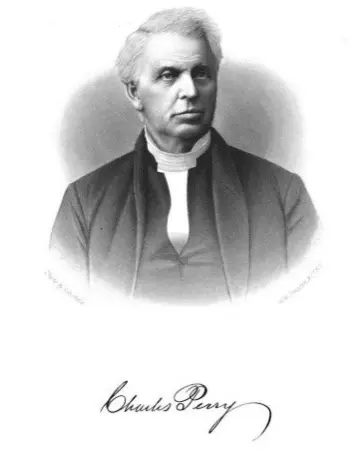

While slavery was not very prevalent locally, there were still citizens in Westerly who were in opposition to the practice being used throughout the country. Perhaps the town’s most notable and ardent supporter of abolition was a man by the name of Charles Perry (1809-1890), a friend of Frederick Douglass, and a well-known opponent of the slave trade.

Charles Perry was born in Westerly on September 27, 1809 to Thomas and Elizabeth (Foster) Perry.[2] Charles was from a long line of Perrys descended from Edward Perry who was born in Devonshire, England c. 1630 and settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony where he became one of the nation’s first Quakers.[3] In 1825, at the age of 15, Charles Perry published what is widely regarded as the first newspaper published in Washington County, Rhode Island, the Bung Town Patriot.[4]

The newspaper was a laborious effort, with Perry carving the type and advertisements from wood blocks on his own. The paper contained poetry, advertisements, news, and shipping announcements among other features.[5] The following year, when he was only 16 years old, Charles Perry succeeded his recently deceased father as the cashier at the Washington Bank (later known as Washington Trust), a position he held for the next 55 years.[6]

Perry was selected by the meeting of directors on March 29, 1826 and was officially appointed at the annual meeting on July 4 of that year.[7] In 1836, Charles Perry was named the Director of the Washington Bank, and upon his retirement as a cashier in 1881, he was named president of the bank.[8]

Perry was also very active in various causes and was “a strong advocate of temperance, an uncompromising abolitionist, and was active in many movements of civic and moral reform.”[11] He was said to have had a deep love of education which led him to be a vehement supporter of improved schools in Westerly.[12]

While Perry believed in a great many causes throughout his life, perhaps his strongest conviction was that slavery should be outlawed in the United States. At his home on Margin Street in Westerly, Perry hosted well-known abolitionists including Benjamin Lundy, and most notably, Frederick Douglass.[13] On December 7, 1868, Douglass delivered a lecture hosted by the Young Men’s Christian Association at the Westerly Armory titled “William, the Silent.”[14]

According to a copy of the lecture maintained by the Library of Congress, Douglass spoke that night about William I, Prince of Orange.[15] One story tells that Perry actually shielded Douglass when a man who opposed the abolition of slaves hurled eggs and water at Douglass during his speech to the Westerly Anti-Slavery Society.[16]

In addition to supporting prominent opponents of the slave trade in America, Charles Perry also actively aided the escape of runaway slaves as part of the Underground Railroad. Perry was known to have harbored fugitive slaves at his home before moving them to his brother Harvey’s home in North Stonington.[17] On his land, Perry constructed a number of stone cottages with sod roofs where the fugitive slaves could hide until their next stop.[18]

According to one tale a runaway slave once showed up at the Perry residence and, wanting to help the man, Charles rolled him up in a rug in the back of a farm wagon and took him to the next stop in Ashaway.[19] Often times, Perry’s Quaker beliefs intersected with his opposition to slavery. In a letter dated September 24, 1845, to his friend, Thomas B. Gould of Newport, a fellow Quaker, Perry refers to anti-slavery lecturer Abby Kelly being carried out of a meeting in Ohio.

Perry, a ‘Wilburite’[20] wrote that he hopes it was Guerneyites (a branch of the Quaker faith that held views opposite of his own) who performed the act.[21] In 1863, Perry and his cousin, Ethan Foster, went to Washington to lobby to President Lincoln in support of four fellow Quakers who were jailed for refusing the Union draft “as a matter of conscience.”[22]

In 1848, Charles Perry married Temperance Foster, the daughter of Thomas and Phoebe (Wilbur) Foster, and a granddaughter of eminent Quaker preacher John Wilbur, the leader of the Wilburites.[23] The couple were the parents to five children, four of whom (Mrs. J. Barclay Foster, Mrs. F.C. Buffum, Charles Perry Jr., and Arthur Perry) were living at the time of Charles’ death in 1890.[24] Temperance (Foster) Perry died on November 27, 1861, leaving Charles as a widower for the final 29 years of his life.[25]

The Perry family was relatively well-off in the middle of the 19th-century. In 1850, Charles owned $2,000 (approximately $65,000 today) worth of real estate in Westerly.[26] By 1870, the value of Charles’ real estate had increased significantly to $30,000 (approximately $582,000 today) while he also claimed to hold $20,000 in his personal estate.[27]

By all accounts, Charles Perry was a well-respected man in Westerly. Although he never held public office in town, he was well-known for championing various causes which he felt passionately about. Even those who opposed these same causes could see the virtue of their opponent. Charles Perry died in Westerly on May 29, 1890 and he is buried in River Bend Cemetery next to his wife, Temperance.[28]

[su_accordion class=””] [su_spoiler title=”Footnotes” open=”no” style=”default” icon=”plus” anchor=”” class=””]

- United States Census Records, 1790-1860, Ancestry.com.

- Obituary of Charles Perry, Westerly Weekly, 5 June 1890.

- Cole, J.R., History of Washington and Kent Counties, Rhode Island, (1889), pg. 352.

- Cole, J.R., History of Washington and Kent Counties, Rhode Island, (1889), pg. 352.

- Cole, J.R., History of Washington and Kent Counties, Rhode Island, (1889), pg. 352.

- Obituary of Charles Perry, Westerly Weekly, 5 June 1890.

- Obituary of Charles Perry, Westerly Weekly, 5 June 1890.

- Obituary of Charles Perry, Westerly Weekly, 5 June 1890.

- Depositions Taken on Behalf of the Defendants in a Suit in Equity between Oliver Earle and Others, Complainants, and William Wood and Others, Defendants, in the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, (Boston, MA, 1850), pg. 27.

- History of Rhode Island, Biographical, pg. 11, Charles Perry.

- History of Rhode Island, Biographical, pg. 11, Charles Perry.

- Cole, J.R., History of Washington and Kent Counties, Rhode Island, (1889), pg. 353.

- History of Rhode Island, Biographical, pg. 11, Charles Perry.

- “Westerly.” Manufacturers’ and Farmers’ Journal, 30 November 1868, pg. 1.

- Douglass, Frederick. “William the Silent” – Folder 1 of 7. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mfd.30005/.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen, The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations, )2015), pg. 409.

- DeSimone, Russell, “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad Rediscovered” Small State Big History, 23 February 2019.

- DeSimone, Russell, “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad Rediscovered” Small State Big History, 23 February 2019.

- Perry, Harvey, “Letter: Underground Railroad story has a family tie” Westerly Sun, 23 January 2019.

- Wilburites were viewed as conservative members of the Quaker faith who adhered to the tents laid out by John Wilbur, the grandfather of Charles’ wife, Temperance.

- Quakeriana Notes: Concerning Treasures New and Old in the Quaker Collections of Haverford College, (Haverford, PA), pg. 5-8.

- Foster, Ethan, The Conscript Quakers, Being a Narrative of the Distress and Relief of Four Young Men from the Draft for the War in 1863, (1883).

- Cole, J.R., History of Washington and Kent Counties, Rhode Island, (1889), pg. 354.

- Obituary of Charles Perry, Westerly Weekly, 5 June 1890.

- Gravestone entry for Temperance Perry, RI Historic Cemetery Commission, https://rihistoriccemeteries.org/newgravedetails.aspx?ID=364508.

- Household of Charles Perry, Westerly, Washington, Rhode Island, 1850 United States Census, Roll: M432_847; Page: 396A; Image: 353.

- Household of Charles Perry, Westerly, Washington, Rhode Island, 1870 United States Census, Roll: M593_1473; Page: 392B; Family History Library Film: 552972.

- Gravestone entry for Temperance Perry, RI Historic Cemetery Commission, https://rihistoriccemeteries.org/newgravedetails.aspx?ID=364508.

[/su_spoiler] [/su_accordion]