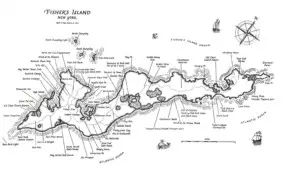

The waters around Fishers Island, New York and out to nearby Race Rock Lighthouse are littered with numerous shipwrecks. One of the deadliest occurred on Thanksgiving Day 1846 when the magnificent steamship Atlantic was driven onto the rocks to her doom. North Hill on Fisher’s Island was the end of the line for the Atlantic taking up to 50 people to their deaths, the exact number is not known.

Standing on a boat I was looking over the scene of that tragedy 172 years later. Three of us, Captain Bill Palmer, his friend John whose boat we were on, and I were here to dive at the site of the wreck. The shoreline is lined with huge boulders that earned it the nickname Stonehenge. I was along strictly as an observer and photographer to record the dive and, except for a swim to cool off, would stay on the boat.

The nearly new ship was on its regular route from Norwich, Connecticut to New York City when she stopped to pick up passengers in New London. A strong gale was blowing as she left the dock just after midnight Thanksgiving morning with over 100 souls on board. Once out in the sound, in spite of the icy blast, her powerful engine drove her through the waves.

The ship shuddered then both her anchor chains parted with a loud crack. Wind quickly pushed the ship toward the rocky shoreline. Passengers and crew donned life jackets and watched in horror as the rocks of Stonehenge loomed in the distance. With tremendous force, the ship struck the rocks quickly breaking up and throwing many into the churning surf. The ships bell, still attached to a mast, swung wildly in the howling wind tolling for the dead and dying.

A New London newspaper described the scene. “Some of the victims were found with limbs gone, caused by the breaking timbers of the boat. Arms and legs were picked up on the shores that had been appendages of persons not recognizable. When the boat first struck the shore, so powerful was the shock, one of the great boilers broke from its fastenings and went high and dry beyond the sea; and strange as it may seem, a little boy was found in it alive.” When the weather cleared ships arrived and helped collect both the survivors and victims’ including Captain Dustan who had drowned.

As the life ring floated out behind the boat on its line it became obvious that it wasn’t long enough to reach the dive site. Another line was tied to the plastic reel and the plastic reel was run out another 100 feet where it floated behind the boat. At the time tying another line to extend this safety line didn’t seem dangerous but it would prove to be an almost fatal mistake.

The day was hot and I’d just climbed back on the boat from a swim when I heard a shout. Looking out I saw a head bobbing on the surface of the water. The head was at least a hundred feet from the life ring. It was John and he was in trouble. “I can’t get back,” he yelled. “The line came undone. Float me a ball with a line.” He shouted urgently. “ Who the hell tied that knot? It came undone.” I could hear the anger in his voice and my heart sank. I was the one who’d tied the knot attaching the line to the reel.

Without a line to grab onto a heavily clad diver can’t swim against that kind of current. John was now almost two hundred feet behind the boat. Bill was still on the bottom totally unaware of the drama taking place on the surface. He was detached from the line as well and when surfacing would also be swept away. The nearest lands were two islands called the Dumplings that were almost a mile away. They lay across Fisher’s Island Sound which is heavily traveled by large vessels that probably wouldn’t see the small head of a diver.

While I was dealing with trying to get John a line Sam, a friend of Bill’s, pulled up and anchored next to us. He was planning to dive with Captain Bill and John. He’d been watching the drama play out and quickly got into his dive gear. “Do you have a line I can swim out?” He asked. “Yes. I’ve got a line.”

Sam swam over. “I’ll swim over and tie into Bill first. Once I’ve secured the float I’ll tie in with my wreck reel and try to reach John. Do you still see him?” Looking out, I searched where I had last seen him but he was nowhere in sight. “I don’t see him.” A sense of panic started to rise in my chest. Over fifty people had died on the Atlantic that stormy night, right on this spot, and I hoped we weren’t going to add another name to the list.

Then I heard a yell from the direction of the shore. It was John. He’d realized the current was too strong to make it back to the boat on the surface so he submerged to the bottom where the current was much less. Using the last of his air he’d just managed to get to shore before his air ran out. Now that his adrenaline had stopped running he was completely exhausted and very upset. “I could have drowned. Who the hell tied that knot? I almost didn’t make it.”

The rest of the rescue went smoothly. Sam was able to reach Captain Bill and tie into the float. The line I gave him was just long enough. The two divers pulled themselves back to the boat. Sam then took the same line to the shore and got John back to the boat.

Here was the moment I had been dreading. The plastic reel was examined by Captain Bill after sorting out the tangle of lines attached to it. Bill looked closely. “Well. I’ll be a son of a bitch. The end of this line was never tied to the reel. It was just a knot slipped over a hook on the inside. We used it before and I guess just assumed it would be tied to the reel but when all the line ran out it just came unhooked.”

“Jesus. No one ever checked to make sure it was right?” said John.

“I guess not,” answered Bill. “I think we learned a valuable lesson today.”

“Yeah,” said John. “Not to use a cheap piece of crap for a safety line.”

So it wasn’t the knot I’d tied. A wonderful feeling of relief came over me. We all agreed that we’d had a close call and things could have gone south in a hurry. It was a good thing Sam had come along when he did because even though John made it to shore he was exhausted and out of air. He wouldn’t have been able to get back to the boat without Sam swimming in the line.

The fog bank that had been drifting offshore cleared and the grim visage of Race Rock Light came into view about a mile away. It’s said that the light is one of the most haunted in the country and the scene of numerous tragedies. Perhaps the ghosts that haunt this place reached out and tried to take another life or perhaps it was just the end of a line not being tied, but none the less we’d had an adventure that I will never forget.