Everybody loves a good mystery and New England has more than its share. One of the most implausible but intriguing legends is what has become known as the Westford Knight. The mystery surrounds a carving on a rock ledge that some believe is evidence that a Scottish Earl, Henry St. Clair, led an expedition to the New World almost 100 years before Columbus.

The first published account of the carved ledge in Westford, Massachusetts was in 1873 in the Gazetteer of Massachusetts and the description read, “There upon its face a rude figure, supposed to have been cut by some Indian artist.” The carving was well known by locals and was thought to be Native American pictographs called an “Indian smoking a pipe.”

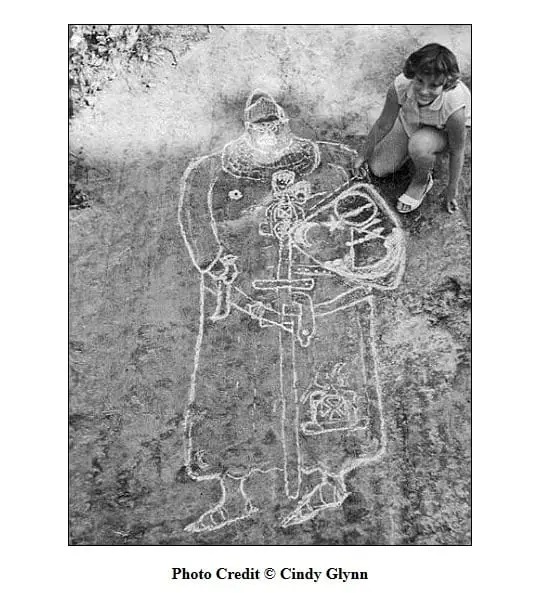

The Glynns’ examined the faint punch marks and little by little removed the dirt and grass which hid the rest of the figure. It was Glynn’s daughter who first pointed out the weathered outline of a knight in full armor with a sword and shield. Glynn initially thought the carving might be of Viking origin.

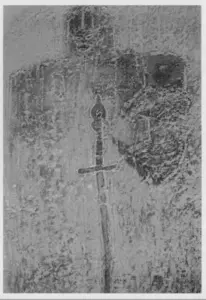

Glynn photographed and took rubbings of the carving and sent them to his correspondent Dr. Thomas C. Lethbridge in England, a well-known but somewhat controversial archaeologist. Lethbridge immediately recognized the carving to resemble funerary monuments from the middle ages in western Scotland. Lethbridge proposed to Glynn that the sword was not of Viking origin but was “a hand-and-a-half wheel pommel sword” common in 14th-century North Britain.

To identify the devices on the shield he referred the matter to an expert in heraldry. The expert suggested that the devices resembled the coat of arms for the Clan Gunn of Scotland. It has been suggested that the knight is Sir James Gunn a Knight Templar who reportedly traveled with Prince Henry Sinclair, Earl of the Orkney Lord of Roslin.

Prince Henry, the story goes, became interested in finding the New World when a fisherman told a remarkable story of having been driven far west by storms until he reached a temperate land peopled by strange natives. Greenland already had settlements and the fisherman’s stories suggested that this new land lay somewhere beyond.

Continuing to explore, Prince Henry left his settlement and proceeded down the coast to Massachusetts. He headed inland sailing up the Merrimac River to where Gunn could have died in or near Westford and Prince Henry ordered a carving as a memorial to him. The carving would have been done by the ship’s armorer using one of his punches to peck out the figure. Part of the image was supplied by the straight scourge marks left by a glacier but a set of parallel punch marks, still clearly seen today, created the hilt of the sword.

Sinclair writes, “The rubbing showed a helmeted knight wearing the habit of the military orders with his shield and his sword engraved on the rock in the formal style of the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century. The outline of the sword has remained strong. It points due north and suggests a ritual burial. It is shown as broken twice below the hilt. The custom of the time was to break the sword of a knight of great courage and distinction and to bury it with his body. The effigy of the Westford Knight is some seven feet tall and depicts a powerful man.”

Sinclair goes on to propose that this inland exploration up the Merrimac River to Westbrook happened as Prince Henry was on his way to Newport, Rhode Island. There he established a second settlement and built the enigmatic Newport Tower as a Templar church, lighthouse, and watchtower. The Templars were a Catholic military order that had been disbanded ninety years before Prince Henry’s voyage.

The publication of Dan Brown’s highly successful novel, The Da Vinci Code, in 2003 renewed interest in the obscure Westford carving and its possible connection to the Sinclair clan. The 14th-century Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland built by William Sinclair, Prince Henry’s grandson, became attached to the Grail legend. A number of conspiracy books have identified the Rosslyn Chapel as a secret hiding place of the Grail. Some also suggest that the Templar treasure could have been carried to the New World on one of Prince Henry’s ships.

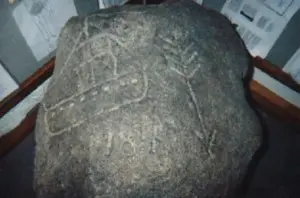

To add even more to the mystery of the Westford Knight, a 250-pound carved stone was found in 1930 nearby when a road was being widened. Groton Road is about two miles from the base of the hill where the Westford Knight is found. The Boat Stone, as it’s now named, has a carving of a single masted ship on it, similar to the ships that Prince Henry would have sailed. There is also the number 184 and an arrow.

In 2007, Forensic Geologist Scott Wolter studied the stone. It was his opinion that the weathering patterns in the carving indicated that the carving was not modern and that the weathering was consistent with that of a 600-year-old artifact. Wolter further determined the carving was made using a “pecking” or “punch-hole” technique with a metal tool, similar to the technique used to carve the Westford Knight carving.

Prince Henry returned to Orkney in 1399 telling stories of the land he had found and making plans to return on a larger expedition. It was not to be, he died fighting English raiders in Orkney in 1400. The documentary evidence for Prince Henry’s voyage remains in doubt as it was largely based on letters written later by the Zeno brothers and much of their account has inaccuracies.

A stone marker nearby reads: “Prince Henry, First Sinclair of Orkney, Born in Scotland, made a voyage of discovery to North America in 1398. After wintering in Nova Scotia, he sailed to Massachusetts and on an inland expedition in 1399 to Prospect Hill to view the surrounding countryside, one of the party died. The punch-hole armorial effigy, which adorns this ledge, is a memorial to this knight.”

Whether the Westford Knight is a natural phenomenon, a Native American pictograph, or a fourteenth century memorial to a Scottish Knight Templar is lost in the mists of history but it still makes a great story. The Westford Historical Society website has more information and directions to the Westford Knight.