I was curious to find out which sculptures are considered the world’s greatest. There are a few familiar ones: Michelangelo’s statue of David, the Statue of Liberty, Christ the Redeemer on a mountain top in Rio, Venus De Milo and The Motherland Calls in Volgograd, Russia but nowhere is the American Volunteer listed. If you live in Westerly and you haven’t heard of the American Volunteer and why it should be on the list of great statues, let me explain.

The American Volunteer, also known as The American Soldier and locally known as the Antietam Soldier, is a colossal granite statue that crowns the U.S. Soldier Monument and forms the centerpiece of Antietam National Cemetery in Sharpsburg, Maryland. The monument is also known as the Private Soldier Monument. The monument was built to honor the brave men who served during the Battle of Antietam.

There were many bloody battles during the American Civil War, one of the worst being the Battle of Antietam. It was fought on September 17, 1862 between Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s invading Army of Northern Virginia and Union General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, near Antietam Creek, Maryland. By the end of the battle, 22,717 Americans lay dead, wounded, or missing. On a side note one of the army generals killed in the battle was Joseph Mansfield that Fort Mansfield, at the end of Napatree Point, was named after.

Shortly after the war, commissioners nominated to commemorate the fallen soldiers at the Battle of Antietam, decided that a monument should be erected at the National Cemetery at Sharpsburg, Maryland. Requests for proposals were sent out and the proposal adopted by the commission was from James G. Batterson of Hartford, CT.

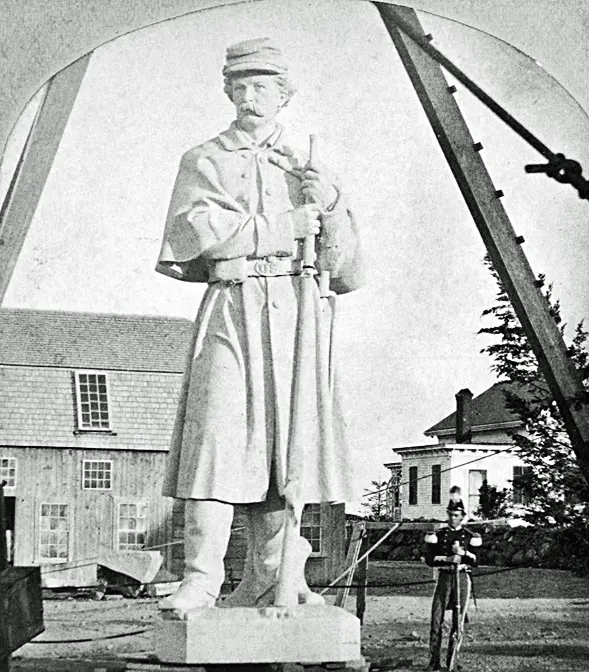

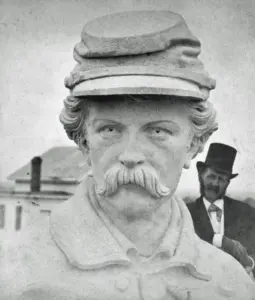

The statue, described as the largest work of its kind in the country, was carved by a team of stone carvers, headed by Pawtucket, RI apprentice stonemason James W. Pollette. Pollette was assisted by sculptor Joseph Bedford. Together they would be responsible for the cutting and finishing of the final product. Both men were young; Pollette was 26 and Bedford only 27 at the time of the statues completion in 1874. It’s estimated that the statue took a total of 4 years to quarry and finish.

The statue was cut from a single piece of granite weighing nearly 60 tons when removed from the quarry. The statue was created in two pieces; it was probably cut into two pieces before the carving started, this would later facilitate shipping. The soldier’s belt hides the joint where the two segments meet and a tree stump at the back of the figure adds stability.

The pose of the statue was unusual for its time. Rather than the formal pose of a soldier standing at attention, Conrads had his figure stand in the informal pose of parade rest. Conrads’s soldier is alert and actively surveying the horizon. With the instantaneous popularity of The American Volunteer, the parade rest pose soon became common for Civil War monuments.

Batterson allowed O. Langworthy & Company to photograph the colossal statue at the Rhode Island Granite Works in Westerly prior to its departure by ship for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. These are some of the photographs in this article; notice Batterson looking over the statue’s shoulder. These photographs were probably intended to generate publicity before its formal debut at the Centennial Exposition in May 1876.

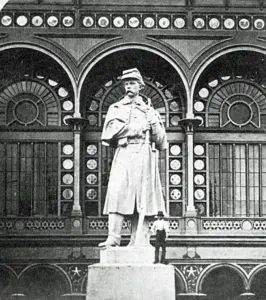

After its debut at the Exposition, the statue was loaded onto a canal barge and transported to Sharpsburg, Maryland. It arrived intact despite one major mishap when the upper half of the soldier fell into the Potomac River. From Sharpsburg, it was carried on rollers to the National Cemetery and installed on a new and taller pedestal, attributed to architect George Keller. The entire monument consisting of 27 pieces of granite weighed 220 tons; the statue stood 21 feet high and weighed nearly 30 tons. The entire colossus stood 45 feet high and weighed over 250 tons. The monument was dedicated on September 17, 1880, the eighteenth anniversary of the battle. The total cost of the monument was over $32,000.

George Hess, the first superintendent of Antietam National Cemetery, wrote in 1890, “In the center of the grounds is erected a monument commemorative to the great event of the battle, and the heroism of those who sleep at its foot and around it. It is the colossal statue of an American soldier standing guard over the remains of the loyal dead, who are buried all around him, with this inscription on the die or shaft: Not for Themselves, but for Their Country, September 17, 1862.” And so the American Volunteer continues to keep watch over his comrades to this day. Certainly, at least in my mind, one of the world’s great statues.