Rhode Island certainly has many characters in its history; pirates, scoundrels, mystics, and rogues. In fact, Rhode Island was referred to as Rouge’s Island by some and was said to be a den of people with proclivities of a fishy nature. This led to the old saying, there’s something fishy about him. One of my favorite colorful Rhode Island characters and a revolutionary war hero is General William Barton.

He was a big man with tremendous energy and was well-liked by officers and enlisted men alike. Barton was appointed second in command of the 450-man Rhode Island militia regiment that was camped in Tiverton on the banks of the Sakonnet River. The regiment was there to protect against the British troops who occupied Aquidneck Island and the city of Newport.

Barton hatched a daring and dangerous plan to capture the British commander Major General Richard Prescott. Prescott was the worst kind of British officer, harsh, arrogant, and demanding. Not only was he hated by the Americans but he was even hated by his own men. Capturing Prescott would be a major coup and would also allow for an exchange for an American captive of equal value. The soldier that George Washington wanted back was General Charles Lee, a former British officer who had joined the American Revolution on the side of the Americans.

It was a risky plan because it meant rowing five whaleboats with his crew of 38 men and 6 officers passed the entire British squadron anchored in Narragansett Bay at night unobserved. Barton learned that Prescott had taken over a large farmhouse owned by a loyalist and although there was a troop of British dragoons camped nearby, he was guarded by only one sentry. There were many men in Barton’s command that were familiar with the area including a giant African-American slave, Tak Sisson that had been raised there.

To help choose the best men to accompany him he devised a whale race on the river and chose the strongest rowers. He called the entire regiment together and told them he was looking for volunteers for a very dangerous mission. Except for Barton, no one knew the plan. Barton told them.

“Those who wish to go with me take two steps forward.”

The entire regiment stepped forward and Barton selected 40 which included the men that knew the area and the strongest rowers.

On the night of July 5, 38 men and six officers boarded five whaleboats, the oars were muffled with sheepskin. They began to row toward Bristol through Mount Hope Bay. A violent thunderstorm came up scattering the boats. It took them 26 hours to make the 10 miles from Tiverton to Bristol where they camped. Because they could only travel at night it took them five days to reach the Portsmouth Shore and the farmhouse where Prescott was located.

Barton and his men walked silently about a mile to Prescott’s headquarters. Luckily, Prescott received a shipment of wine that day and had been drinking heavily. Leaving his men outside Barton, along with a soldier named Hunt, and the ex-slave Tak, approached the front door.

“Who goes there,” the sentry challenged.

“Friends,” answered Barton.

“Advance and give the password,” the sentry replied.

Barton answered, “We have none. Have you seen any deserters?”

But before he could answer the giant arms of Tak grasped him.

“Not a sound or you’re a dead man,” Barton warned.

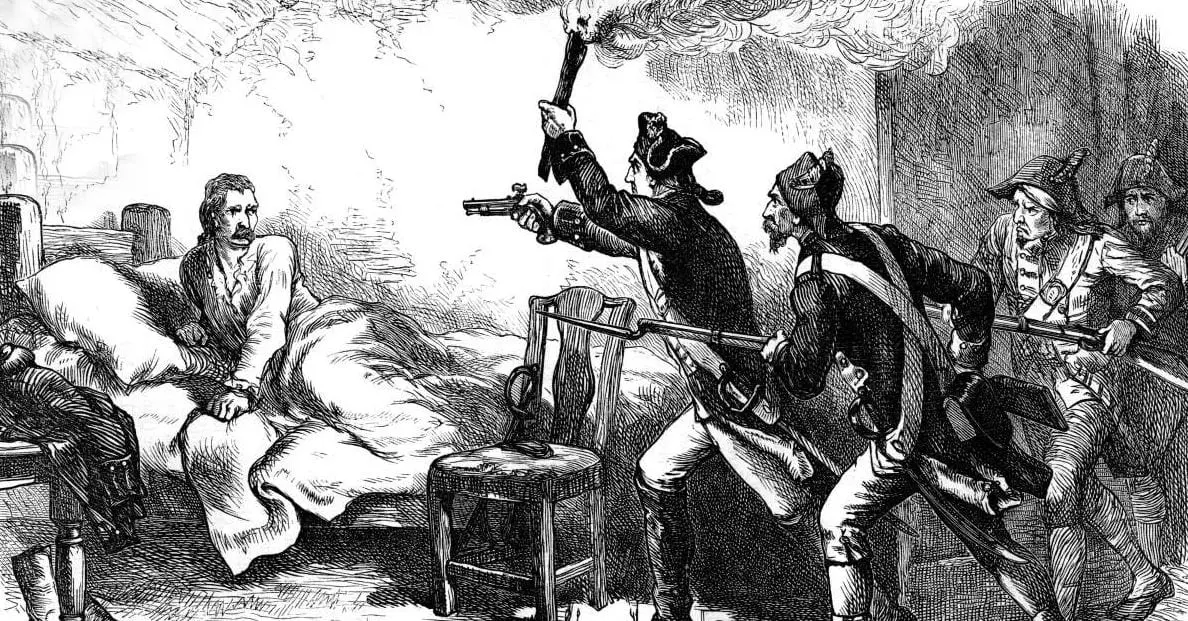

The men quickly entered the house and went looking for Prescott.

Upon entering the bedroom Barton saw a short, gray-haired man sit up in bed.

“Are you General Prescott?” Barton demanded.

“I am,” answered Prescott.

“You are my prisoner sir,” the general answered, “I acknowledge it, sir.”

Barton was anxious to make his getaway with his prisoner. The general, in only a nightshirt, was wrapped in a blanket and pushed from the house. He’d tried to pull on a pair of trousers but was taken away without them. The cranky old general demanded that they send back for his shoes, trousers, and sword. Finally Barton, in frustration, asked Tak to go back and get the generals trousers and sword. The general looked at Barton and said, “You have made a damn bold push tonight.” And indeed the exploit was a remarkable accomplishment.

Before dawn the whaleboats passed by the British fleet and landed at Warwick Neck. General Prescott was put on a stagecoach, under heavy guard, headed for Providence. The capture of General Prescott was the best news George Washington had received in a month. Word quickly reached England about how the general had been captured without his pants. This was highly embarrassing to the general and the British. The London Chronicle described the debacle with a poem.

What various lures there are to ruin men:

Woman the first and foremost all be witches,

A nymph thus spoiled a General’s mighty plan,

And gave him to the foe without his britches.

For the capture of General Prescott the Continental Congress awarded Barton with a sword and passed a resolution honoring his service. The Rhode Island General Assembly awarded Barton $1,120 which he magnanimously split with the 40 men who helped him.

After retiring he moved to Vermont and founded the town of Barton. He became involved in a land dispute and was successfully sued in court. Ever headstrong and stubborn he refused to pay the small assessment of $272 and he was ultimately confined to jail at a local inn in Danville for 14 years. Barton would be locked up at night after he’d gotten free drinks from the crowd by regaling them with his exploits. At the age of 77 he was released at the initiative of the visiting Marquis de Lafayette who agreed to pay the balance of his debt.

The Pawtucket Gazette wrote: He was a venerable old soldier of the American Revolution. For true patriotism and unwavering courage, few men were more distinguished. Full of years and full of glory the old soldier has been gathered to his fathers. His last march is finished and he sleeps in that tent which sooner or later is pitched for all mankind.